Previously in Miller Avenue Musings: My sister Nell had visited from London with her one year old son Poggy. It was a very happy occasion and I made plans to go back to work on the San Francisco waterfront to save for a trip to London.

All through my madness I’d been high as a kite, confident and sure of myself, but now the hubris began deserting me. Doubt and darkness settled on my shoulders like ashes from above. In coming down from the tremendous high of thinking I was the messiah, here to save the world, I kept on going down into what would prove to be a total nervous breakdown. I had never contemplated such a fate and suddenly I was trapped within its walls. There was no talking my way out of this one. It wasn’t going to be better in the morning. I gradually became separate from the world around me.

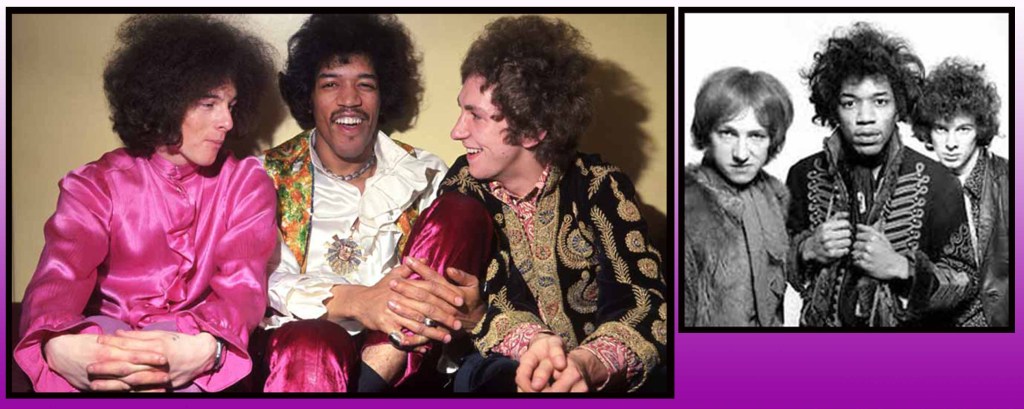

There were still small slivers of light. My old friend popular music continued to look after me. The record player in my bedroom was constantly in use and I had a sizeable collection of LPs that I listened to. Before I went crazy I had purchased the album Are You Experienced by the Jimi Hendrix Experience. The Beatles record All You Need Is Love came into the Top 40 and I heard it on the radio but on my record player I listened to the Hendrix disc over and over.

The late Jimi Hendrix is mostly remembered for his electric guitar playing but as I listened over and over to that album I concentrated more on his words. The subject matter in Hendrix’s lyrics dwelt on psychological problems, things I was beginning to experience. One song was entitled Manic Depression and in it he described being unable to adapt to the world around him. Manic depression was a concept I’d known nothing about. I was, however, sliding into the grip of a severe manic depression. So I immersed myself in the wailing music of the Jimi Hendrix Experience.

The Jimi Hendrix Experience featured bass player Noel Redding and drummer Mitch Mitchell.

When I first saw Hendrix’s trio play at the Fillmore and on a flat bed truck in the panhandle, his hit on the radio was Purple Haze. Now when I listened, I heard his lyrics in a very different way. Whatever the Purple Haze was, he didn’t seem happy that it was physically surrounding him and he plaintively cried “Help Me,” a few times during the song. I didn’t wonder at the time if he too, had had a nervous breakdown but his lyrical disposition on that album’s material lead me to conclude that he had. The song I Don’t Live Today articulated perfectly my mental condition in the months to come as the emotional distance between myself and the real world grew and grew.

The image of the Jimi Hendrix Experience was carefully created and nurtured by their manager, ex-Animal, Chas Chandler.

The world outside my bubble of depression continued to turn in spite of the fact that I knew nothing about it. The Vietnam war was dividing the nation in a big way and President Johnson’s policy of bombing North Vietnam was losing him support within the Democratic Party. After Johnson’s re-election as president in 1964, Bobby Kennedy resigned as his attorney general and became a critic of the Vietnam war. I remember a good friend predicting that Bobby would make ending the war his cause as a pathway to the presidency. Maybe that is what he would have done had he lived until the next election.

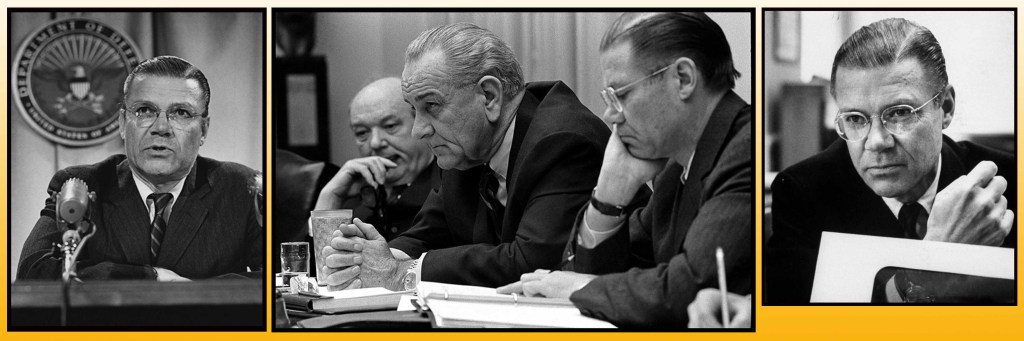

But for now Johnson was committed to bombing North Vietnam though, in the oval office, he seemed to be trapped between hawks and doves. In early September he denied there was any division within his cabinet about war tactics. The press was reporting that Defence Secretary Robert McNamara was in conflict with military chiefs who wanted him to escalate the bombing but at a hastily convened press conference Johnson denied this. A reporter asked Johnson if McNamara had threatened to resign if the bombing was stepped up and the president described that as “absolutely” untrue. “That is the most ridiculous report I have seen since I became president.”

Three photos of President Johnson’s Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara. Pictured in the centre photo is Secretary of State Dean Rusk, Johnson and McNamara.

But not all the criticism was coming from his own party. George Romney, the Republican governor of Michigan became critical of the war. Romney was positioning himself for the nomination to be the Republican presidential candidate in 1968 but he was not alone in that ambition. Ronald Reagan, who had become governor of California also had his eye on this prize.

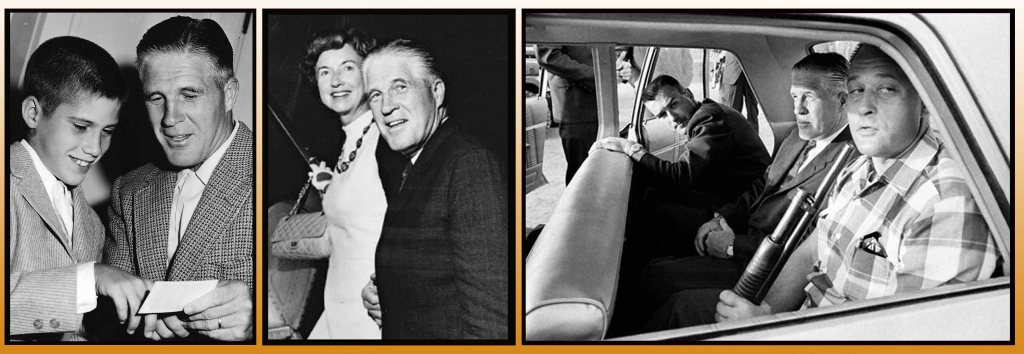

George Romney was the governor of Michigan who, along with Ronald Reagan, sought the Republican presidential nomination for 1968.

In pursuit of the presidential nomination, Reagan stated that the U.S. should be prepared to use nuclear weapons in Vietnam, echoing opinions expressed by Barry Goldwater in 1964. Such talk was popular with gung-ho supporters of the war. As governor, Reagan was a passionate slasher of budgets and his recent cuts to the Medi-Cal program for the poor were ruled illegal by a superior court judge. Blackie had met Reagan back when he was a Roosevelt liberal and judged him, at that time, to be a “phony.” Of course Reagan had shed his liberal credentials in 1947 when the House Un-American Activities committee came to Hollywood. He jumped on the anti-Communist bandwagon, testified to the committee and sang like a bird to the FBI naming many names.

But that was 1947. Twenty years later in 1967 and Reagan was now governor of California. His rival Romney was out on the trail drumming up support for his own nomination and probably should have chosen a different venue for his outdoor breakfast than Watts, the area of Los Angeles which had seen serious race riots in 1965. Two articulate young black men, Tom Jacquette and Lou Smith, grilled him relentlessly on several issues, one being his support for Ronald Reagan’s cuts to the Medicare programme. The two young men put Romney squarely on the defensive.

Governor Romney with his son Mitt, his wife Lenore and sandwiched between two armed police officers as he visited the site of the Detroit riots in 1967.

In early August, nineteen Tam High students from Marin City headed for Los Angeles to attend the second Watts Summer Festival held to commemorate the riots which had occurred there. “The whole purpose of this trip,” said Lanny Berry, leader of the six-day trip, “Is to show the Negro kids how many constructive self-help programs have developed in Watts. The festival is one of them.”

Helping Berry organise the self-help trip was Douglas Quiett, also from Marin City, and now a group counsellor at Marin Juvenile Hall. Quiett, had organised the picketing of two Mill Valley realtors for CORE in 1963 as they were not obeying the recently passed Rumford Fair Housing Act.

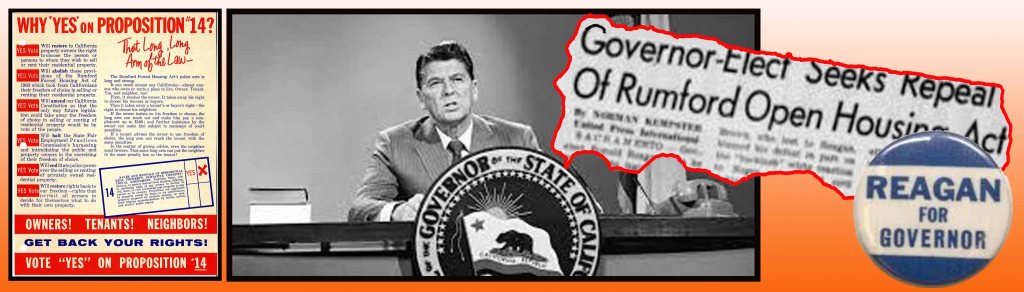

The forces of racial separation were not going to let the Rumford Act go unchallenged. A group called Americans to Outlaw Forced Housing initiated a petition to repeal the Rumford Act and the Marin County Real Estate Board decided to make the petitions available through their office. Though their spokesperson denied that the board was endorsing or condemning the repeal initiative, their supply of the petitions was seen as an endorsement. Enough white voters in Marin and other counties in California went to their real estate board offices to collect and sign the petitions which put Proposition 14 to repeal the Rumford Act on the ballot that November. The proposition was then passed with a majority of over 1.5 million votes.

The passage of Proposition 14 highlighted a deeply engrained racial bias in the white majority of the state of California. The Los Angeles Times endorsed it, saying that housing discrimination was a “basic property right.”

The fight to defeat Proposition 14 was ultimately unsuccessful.

However, Proposition 14’s passage into law hit two major obstacles. First the California Supreme Court in May of 1966 overturned the measure and then the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in May of 1967 that California voters had violated the federal constitution in 1964 when they overturned the state’s open occupancy laws.

The Independent Journal’s headline announcing the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision that proposition 14 was a violation of the constitution.

Ronald Reagan, as part of his campaign for election as governor in 1966, had supported outright repeal of the Rumford Act. In the light of the Supreme Court’s decision in Washington, he modified his approach. Speaking to the California Real Estate Association at their conference he promised to work for repeal of the act or to change it to the point “where it was no longer discriminatory and oppressive.” Reagan denied any racism on his part, saying that his objections to the act should not be taken “as endorsement of bigotry and prejudice or the practice of discrimination.” However his words, objecting to the Rumford act, sent a coded message to white people all over the state who wanted to keep black people out of their whites only towns.

Ronald Reagan made his opposition to the Rumford Act a key part of his campaign to become Governor of California in 1966.

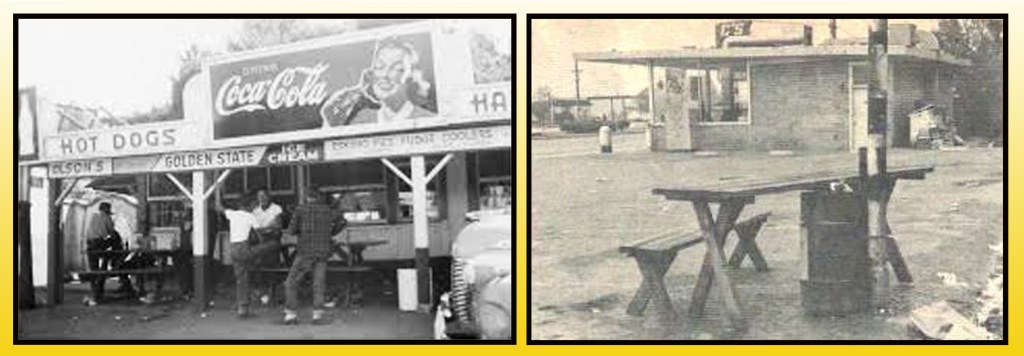

Apart from the Collins family who lived high up on Summit Avenue, Mill Valley was just such a whites only town during my childhood there. It wasn’t until I got to high school at Tam in 1961 that I encountered black students from Marin City. The tough black guys congregated in the inner restaurant section of The Canteen, a building which stood across the street from the lower gate entrance to the back parking lot. At recess, students who smoked all went through that lower gate to light their cigarettes off campus. The white students stood around the front of the Canteen while the black students gathered inside the restaurant section. This organic apartheid between tough white guys and their black counterparts meant they didn’t mix socially.

An appreciation of recent local history was not prevalent in Mill Valley at this time. I had heard my parents say that Marin City came about as housing for ship builders during the war. What I didn’t know was that prior to world war two there were no black people in Marin County at all and that many had come north from the deep south to work at Marinship during the war. Once the war was over the employment vanished. This migration probably explained why the kids from Marin City all spoke with southern accents.

On his first day as a freshman at Tam High, a good friend of mine from Mill Valley was attacked by a black male student in the boys’ locker room. Thinking my friend had made rude remarks about him, the black fellow, who was bigger, punched him in the face repeatedly.

During my sophomore year I shared a gym class with my good friend Jared Dreyfus. At the end of class a black guy picked up Jared’s towel and walked to his locker. Jared went over to him and said it was his towel. The guy gave it to him and no more was thought of it. When Jar and I left the locker room and came around the corner, there was this same black guy with two friends standing behind him. “You called me a ni**er!” He shouted and threw a punch at Jar. The punch landed on Jared’s arm as he raised the binder he was carrying to shield his face. Jared shouted loudly: “I didn’t call you anything and I’m not going to hit you back!” The guy made his accusation again and landed another punch followed by Jar repeating his shouted statement. This went on for about four more punches. Finally it stopped and the black student and his friends walked away.

The N word was highly emotive. I recall one Sunday afternoon at the Sequoia when a group of about five black kids from Marin City attended for the movie that was on. Sunday matinees at the Sequoia were never full and this group of black kids were pretty noisy so I could hear clearly what they were saying between bits of film. They were using the N word a lot, calling each other by it. But if a white person was to use that word there would be trouble. Whenever there was racial tension at Tam High it usually started because someone had scrawled the N word on the inner wall of the Canteen.

Two hangouts for tough students at Tam High. On the left is The Canteen and on the right is C’s Drive-In on Miller Avenue.

C’s Drive-in, just up from Tam High on Miller Avenue, was where the tough white guys in Mill Valley hung out. Most greasers drove their cars to C’s and when racial tension was in the air, the white tribe would gather at the drive-in. If the fights occurred at school they were usually in the back parking lot near the Canteen. And a fight would bring cop cars from all over the county with sirens wailing.

The N word was never uttered in the Myers household. My mother Beth was a passionate anti-racist and would not tolerate such talk. She had been to the deep south as a journalist and had actually witnessed lynchings of black people so she had no illusions about where the attitudes of racism could lead.

We always knew about the Collins family being the only black people in Mill Valley but, though Chuck Collins and I were the same age, I didn’t actually become friends with him until late in my time at Tam High. Chuck didn’t speak with a southern accent like the kids from Marin City. His dialect was the same as all the others in Mill Valley. He had gone to Old Mill School at the same time that I went to Homestead. When I finally did get to know Chuck, we had a conversation in which he told me just how painful it was to hear a white person use the N word. I have never forgotten that conversation. Also lodged in my memory is the Lenny Bruce routine he performed in a nightclub in which he used not only the N word but every offensive epithet to describe Jews, Italians, Puerto Ricans and any other minority group. The point he was making was that if you took the poison out of the word you were left with just a word. However what Chuck had said has kept me from ever using the N word.

But here I was listening over and over to the music of Jimi Hendrix. I was looking for guidance in the words he sang: asking if I was experienced and somehow it seemed like a challenge. I took his words about “coming across to him” as a dare to go to England. I looked for guidance and somehow found it in the lyrics of Jimi Hendrix.

But to get the money to travel to England I would have to go back to work on the waterfront and that meant getting myself into shape psychologically. I had moved into a new phase of my craziness in which it became necessary to disguise my inner thoughts. Blackie would have to be satisfied that I wasn’t crazy anymore and that wouldn’t be easy.

To be continued…

Amazon USA

https://www.amazon.com/dp/B085QN73VQ