Somewhere in the midst of my comedown and the start of my depression, my childhood friend Robbie Bridges, appeared and invited me to go on a road trip to southern California. Robbie was the son of Harry Bridges and he and I used to play together when we were very young. After his parents’ divorce, he’d been living back east with his mother Nancy. He was now based in San Francisco and doing some kind of a white collar job which was nothing to do with Harry or the longshore union.

Robbie must have known what I’d been through the past few months but my memory of our drive down the coast was that we talked as if nothing had happened to me and I responded well to this. Everybody around me at this time was treating me with tremendous delicacy and somehow Robbie not thinking there was anything wrong with me was liberating. At one point he asked me to drive and I did. It was an exciting moment of self discovery to learn that I actually knew how to drive a car.

He told me all about the pop music he was keen on. He was particularly taken by The Who and told me about gigs he’d been to. I cannot remember where we stayed on this trip but I think we were away from San Francisco for a few days.

A little bit of logical thinking was seeping into my fevered brain. The idea of a trip to England, became something I felt I had to do. I knew that in order to get the money for such a journey, I would need to go back to work on the waterfront. But to do that I would have to pull myself together and make accommodations with the world around me. For someone who, a mere six weeks earlier, had been stomping around the psychiatric wards at Napa State Hospital insisting that John Lennon was in the next room, this was something of a tall order. But at every point on my journey of madness, I had responded to the signals around me and the fact I had two contacts in London: my sister Nell and my friend Jo Bergman, I took as just such a signal. It did, however, require some organisation on my part.

That I had the opportunity to work on the waterfront as a ship’s clerk was a privilege indeed. This privilege came to me as a result of being Blackie Myers’ son. I was aware just how sought after the clerking jobs on the front were. For starters they paid very well indeed and it could be more than a bit interesting, particularly when you worked down inside the hold of a cargo ship.

Had I never worked on the front before, the prospect of clerking would have terrified me, but the waterfront was a world I was familiar with having done it a fair bit. However this time was different. The recent experiences I’d been through had taken me into dimensions outside the social boundaries of normal society and I realised I’d have to conform to my father’s ways. The first thing would be to cut my hair and dress in a sober manner. There was a huge prejudice against long hairs on the front and, after several months of being a hippie mental patient, my hair was long indeed. My father was a very respected guy up and down the Embarcadero and I knew that it would be disrespectful of me to behave in any way which upset or embarrassed him.

Blackie with his brothers Billie and Harvey in Brooklyn(left), Blackie at his desk in the NMU, and Blackie on Market Street with a seafaring friend.

Also it was very important to be conscientious in the work, which wasn’t really that difficult but accuracy was essential. Blackie always stressed the importance of doing your job to the best of your ability. The reason he always gave for this was to protect the union. After all that was his history. He was a sailor by trade and had helped build the National Maritime Union which was no cake walk. Whenever they tied up a ship and went on strike they were up against all the forces that the ship owners had at their disposal: the police, the national guard, and gangs of strike breakers known as Goon Squads. The fight to build their union had been long and bloody. A few of Blackie’s comrades had been killed in the struggle and while he and his sailors were building the NMU on the east coast, Harry Bridges was leading the longshore union on the west coast.

From left: Blackie Myers, Harry Bridges, Vincent Hallinan.

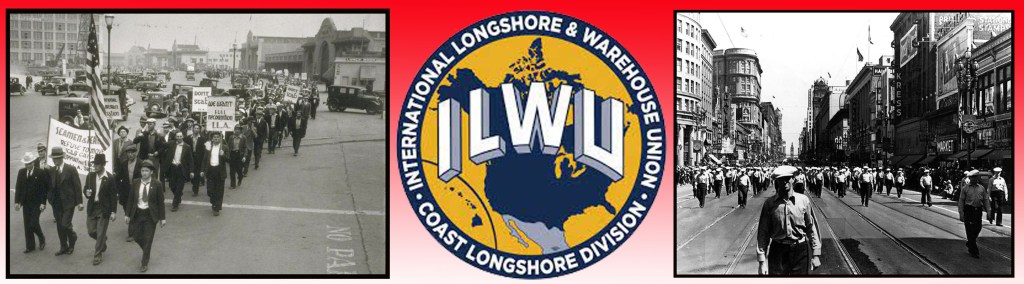

The west coast longshore strike of 1934 was a crucial turning point for the American trade union movement. The police, firing live rounds at the striking stevedores, injured many and killed two. The union held a funeral march for the two dead men which processed up Market Street. Thousands of people lined the street to watch. This was a major factor which led to a general strike.

How the Hearst press Examiner reported the first days of the 1934 longshore strike.

The 1934 strike was the beginning and the original union, the ILA, became the ILWU (International Longshore & Warehouse Union). Their militancy improved working conditions and wages for ordinary labourers. But it also made Harry a target. Those that felt the working class should know their place conspired against him. He was, after all, an Australian by birth, and the federal government would do their damndest to deport him. But that was in the 1930s.

From left: the 1934 longshore strike, the ILWU logo, the longshoremen march up Market Street in 1939.

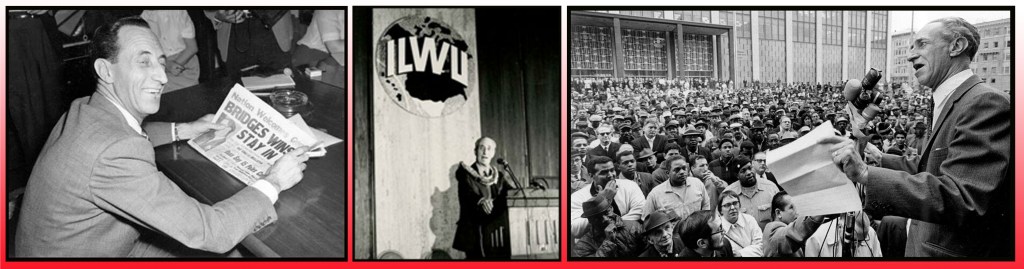

From left: Harry getting good news, speaking at a conference, and speaking to a large crowd in San Francisco.

In 1952, the Myers family had travelled all the way from Connecticut to California because every job Blackie managed to get on the east coast would last only as long as it took the FBI to turn up and tell his employer what a dangerous radical he was.

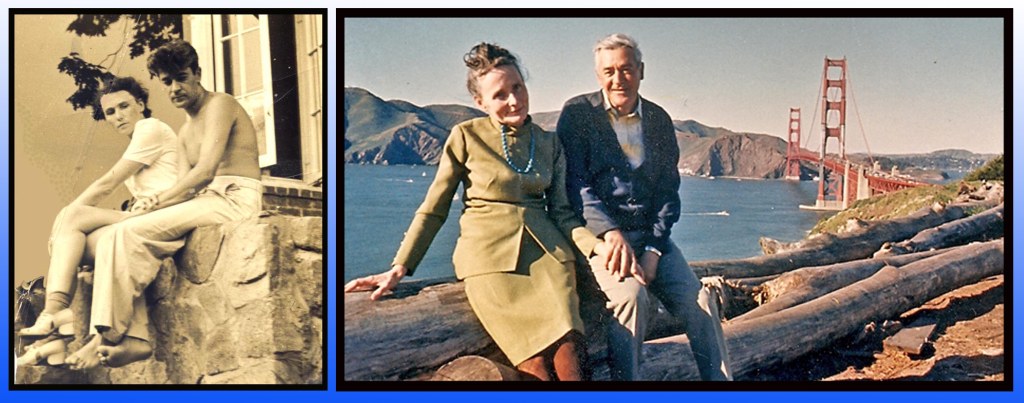

The last leg of our journey west was from Taos, New Mexico to Mill Valley. All of us, Blackie, Beth, Nellie, Katie, Jimmy and I were bleary-eyed from the endless stretches of highway but when we crossed the Golden Gate Bridge and climbed Waldo Grade, the end was in sight. Turning left off Miller Avenue at the 2am Club, we drove into Homestead Valley where a welcome party for us was in progress at Bob Robertson’s house. Bob was an executive of the longshore union, the ILWU. Every family friend we would know in the town we were destined to grow up in was there. The Dreyfus family, the Hallinan family and the Bridges family along with the Goldblatts and the Cox’s. It was such a friendly gathering of people and I instantly thought of all these folks as family.

The reason we had come west was the possibility of work for Blackie on the San Francisco waterfront. Harry Bridges and Blackie Myers were trade union comrades of old. However it took some time before Black was allowed to work on the front. With hindsight, I think the delay was possibly because Harry, with all the political persecution he was continuing to suffer, felt nervous about provoking the federal government. After all Blackie had been a prominent trade unionist in New York and was an early target of the witch hunters.

Beth and Blackie pictured on the left in Connecticut in 1950 and on the right in San Francisco in the 1960s.

From left: Johnny Myers with Blackie in Manhattan, centre: Jimmy. Blackie & John, on the right Johnny, Blackie, Jim and Totem our cat.

Harry was born in Melbourne, and had gone to sea at a young age, winding up working on the docks in San Francisco. The federal government had tried repeatedly to prosecute and deport Harry, claiming he’d lied about not being a member of the Communist Party.

The propaganda of the post war anti-Communist era was very powerful indeed. Hollywood fell in line with the government by creating a blacklist for writers, directors and actors who wouldn’t cooperate with the House Un-American Activities Committee. The cooperation the committee required was to name names of those who either were Communists or fellow travellers. The Hollywood Ten all went to prison, Alger Hiss too went to jail and in 1953 the Rosenbergs were executed for treason so by that time the terror in the country was pretty substantial.

The House Un-American Activities Committee featuring a young Richard Nixon on the right and J. Parnell Thomas in the centre.

Pressbook advertising for the 1951 Warner Brothers film ‘I Was A Communist For The F.B.I’

For Americans who have grown up believing the propaganda of the McCarthy era, the image of a Communist was a ruthless person with shifty mannerisms and dishonest tendencies. Many of my parents’ friends were actually party members but none of them behaved remotely like that. Humour played a big role in most of those friendships.

Blackie had a mischievous sense of humour and was what he called a pork chop socialist. Whatever put food on the table was what motivated him and he was always fair with others. During the depression he found himself in a town where they had a fist fight contest with a prize of ten dollars for whoever won. Handy with his fists, Blackie fought the guy and beat him, but then split the money with his opponent. When I asked him if he was tougher than the other guy, his answer was: “No. I was hungrier.”

As kids, we always enjoyed Blackie’s performances. He was a very good mimic and did a pitch perfect impersonation of Harry, who he always called The Nose.

There were party members who did behave in a stereotypical secretive way but none of my parents’ friends were like that at all. One such person was our neighbour, Dennis Brogan’s grandmother Jean. She used to bring us her copies of The People’s World newspaper and my memory of her was that she was completely humourless.

The American Communist Party became a political force in the early days of the Great Depression. President Franklin Delano Roosevelt had no qualms about dealing with Communists. His administration had many advisors from all avenues of left wing politics including the NMU, and Blackie was one of them. A family friend, Albert Kahn, wrote in his book, High Treason, quoting FDR just after his electoral victory in 1932: “Coming back from the west last week, I talked to an old friend who runs a great western railroad. ‘Fred,’ I asked him, ‘what are the people talking about out here?’ I can hear him answer even now. ‘Frank,’ he replied, ‘I’m sorry to say that men out here are talking revolution.’”

Blackie had gone to sea at age fourteen and became an able bodied seaman. Following the Wall Street Crash of 1929 and the great depression it had caused, he was often out of work and would “grab a handful of boxcars” to get from one port to another in search of a ship to sign on. The hiring halls in every port were referred to as Fink Halls as sailors would have to bribe the man handing out the jobs. The pay was low and working conditions on the ships were often dangerous. Blackie was a tough guy who during those years was both hungry and angry. It wasn’t until he became involved with those working to organise as a union that he was able to channel his anger in a constructive way.

But the fights ahead were deadly dangerous as the shipowners perceived the formation of the union as a direct attack on their interests and deployed all their weapons. The NMU organised strikes on the east coast and ports in the Gulf of Mexico and not one of them was won easily. In addition to the brute force of the military, police and goon squads, the shipowners also had the help of press barons like William Randolph Hearst whose newspapers utilised highly effective anti-labour propaganda. One of Hearst’s papers was the San Francisco Examiner, whose readers were told on a regular basis of what an enemy of the state, Harry Bridges was. During the 1934 strike the Examiner described the strikers as rioters, and celebrated the National Guard and police as heroes defending decent citizens. The fact that they were firing live rounds at unarmed workers was celebrated as protecting the interests of decent society.

People who aren’t too clear on their history often mix up the House Un-American Activities Committee with the senate committee of Joe McCarthy but the two are separate. The House Committee began stirring things up in 1947 while Joe McCarthy didn’t discover Anti-Communism as a cause until 1950. Once he did, he went at it with a vengeance, grilling ordinary citizens on television about petitions they might have signed years before or meetings they may have attended.

Blackie and Beth had been popular folks about town before he was blacklisted but after that, people they’d known pretty well would pass them on the streets of Manhattan without a glimmer of recognition.

He told me later that he truly hadn’t seen the red scare coming. But the signs were there. As an advisor to the U.S. Government on labour relations during World War 2, he was sent into Germany with the occupying troops in 1945. He told me he’d had a meeting with General Patton not long before the accident which killed him. After they’d dealt with their business, Patton poured them each a snifter of the finest brandy and held his glass up in a toast, saying: “Now that this is over, we’re going to get you bastards.” Black told me that he just laughed. But soon after his return to the U.S. his passport was taken away from him. A sailor without a passport cannot work as a seaman.

The choreography of the cold war was designed with military precision and one of the most important weapons was propaganda. Convincing the American public to forget about the Germans, Italians and Japanese being their enemy and to concentrate their fear on the Russians, was essential to this endeavour.

They were helped in no small part by the hearings held by HUAC and Senator McCarthy but also by Hollywood and those who controlled the media. People with left wing or liberal tendencies during the 1930s and 40s suddenly found themselves perceived as highly suspicious individuals and began running for cover. Many of them became stool pigeons and turned on their friends. The fifth amendment, which protects citizens from incriminating themselves, was seen by the newspapers as an admission of guilt and people who took it often lost their jobs.

But the machinations of the federal government didn’t work on my parents and their close friends and I grew up hearing fantastic trade union tales from the 1930s and 40s.

So here I was, fresh out of Napa Hospital, preparing myself for going back to work on the waterfront and yet there were still a few hoops which I had to jump through. True, I wasn’t over my crazyiness but was capable of putting on a reasonable appearance of “not so crazy.” I continued taking Thorazine, but in smaller doses. I went to the barber shop and got my hair cut short. I started shaving regularly and dressing in a conservative way. When Black was convinced I was okay he told me he’d had a word with Johnny Aitken who was the dispatcher in the hiring hall and when I felt up to it I could turn up for work.

To be continued…

Amazon USA

https://www.amazon.com/dp/B085QN73VQ