The Beatles launching their LP Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band.

Some person said: “If you can remember the 1960s, you weren’t there.” I have no idea who made this statement but from my point of view it’s wrong. I was there and I do have very clear memories of a lot of it and in 1967 I was a 20 year old hippy poster artist who went crazy on LSD and wound up in a mental hospital during the Summer of Love. So if I can remember it, anyone can.

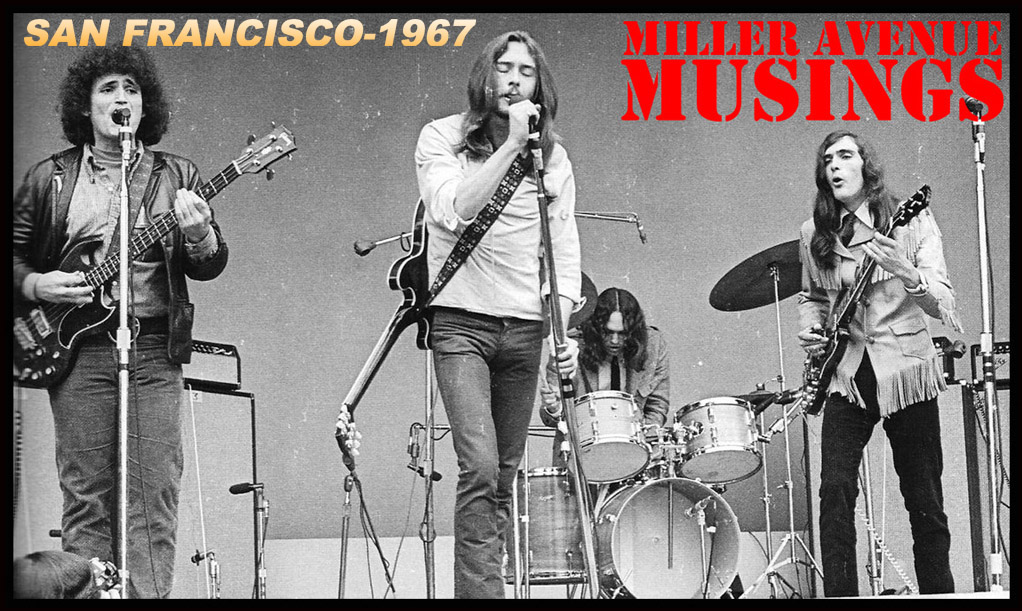

That summer in the bay area, was very eventful. Large outdoor rock festivals began happening, a manifestation of the fact that lots of young Americans were adopting the hippy way of life, albeit for a short time.

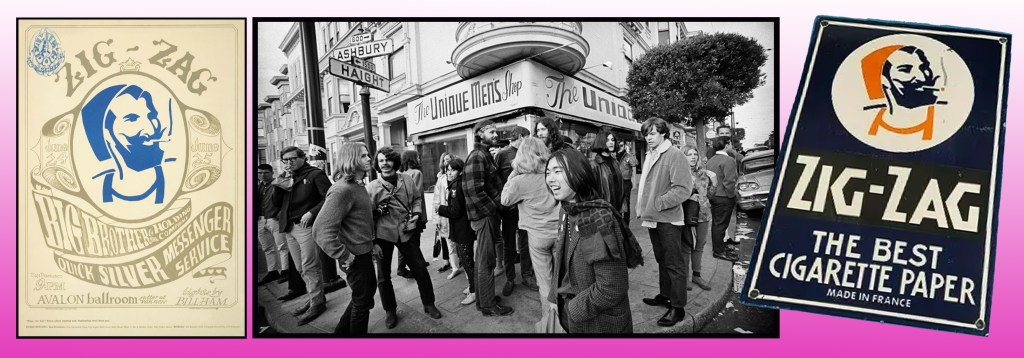

Haight Street in San Francisco was throbbing with hippies and head shops. What my father Blackie would describe as guerrilla capitalism was everywhere with long haired drug dealers on every street corner whispering coded pitches to passing strangers. A good friend of mine went there to score a lid of grass and had to follow the dealer up to his apartment. Once inside the guy pulled a gun on him and demanded all his money. My friend extracted a meagre ten dollar bill from his wallet insisting it was all he had. He lived.

On Haight Street the sidewalk was packed with long haired young men and even longer haired young women. A constant refrain of ‘Spare change?’ could be heard up and down the street from weary looking young people. Psychedelic posters for dance concerts at the Fillmore and Avalon decorated many windows and the Zig-Zag Cigarette Papers logo adorned posters, T-shirts and coffee mugs.

But the most defining event of that summer was the release of the Beatles’ LP, Sgt. Peppers Lonely Hearts Club Band. This album instantly became a hit with everybody I knew. Each house I entered, for the longest time, had this record playing. On the front cover was a colour photo of the four Beatles wearing brightly coloured old fashioned marching band uniforms, standing in front of a big collage which featured pictures of a wide variety of characters including Karl Marx, Marilyn Monroe and Edgar Allan Poe.

The music seized your attention right from the start: the rock band opening of the title track with George Harrison’s bee-sting guitar notes and Paul McCartney’s athletic vocal. It proceeded to take you on a journey of many different musical styles with full orchestral backing and new surprises each time you listened. And the lyrics were so very good. The words to She’s Leaving Home, Fixing a Hole and With a Little Help From My Friends were intelligent, sensitive and they made you think. McCartney’s lyrical optimism was countered artfully by Lennon’s cynicism. Also for the first time these guys seemed to be reflecting on what it was like to be a Beatle. Lyrical references to newspaper taxis and silly people who don’t get past their doors, gave shape to the Beatles’ recent history of an entirely unprecedented celebrity which they’d been living through for the past few years. And here they were in the midst of the hippy era seeming to be more relevant than ever.

This was the very same foursome who provided most of the soundtrack to my teenage years. Their music and lyrics spoke directly to me and my generation about the agonies and joys of young love, lust and all the satellite subjects which concerned their audience of acne-ridden adolescents. From their arrival in the USA in early 1964, I, along with millions of young people all over the world, followed their musical output devotedly, learning each of their songs by heart and singing them out loud with my friends at surreptitious drinking sessions.

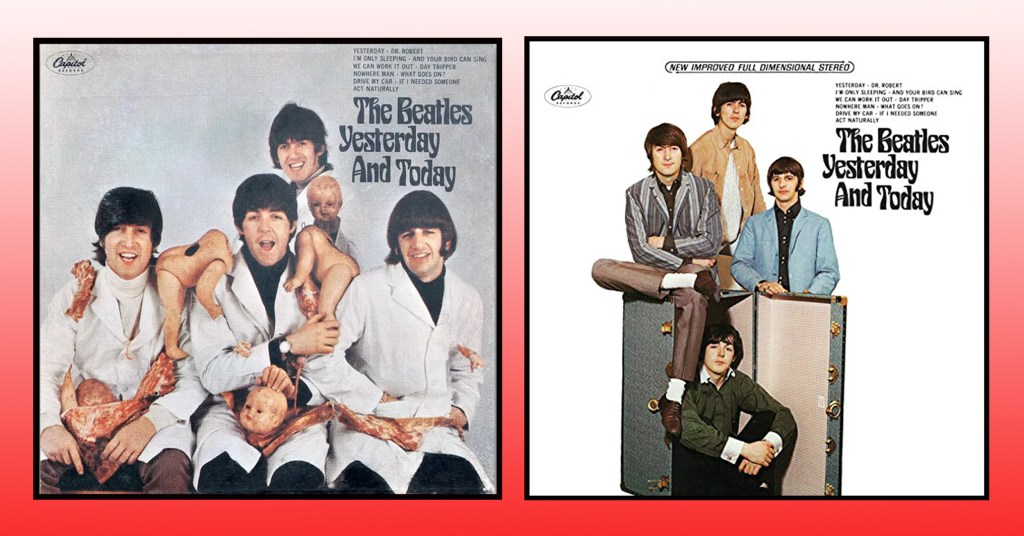

But unlike other showbiz fads, they simply didn’t fade away. They got better. Rubber Soul was their first LP which illustrated the point that they were definitely not a flash in the pan. Their talent was something special which stood the test of time. Then in 1966 they produced Revolver which continued to break new ground with songs like Eleanor Rigby, Taxman and Got to Get You into My Life. During that year they also found themselves mired in controversy. John Lennon gave an interview to the London Evening Standard in which he predicted that Christianity would die out and said that “we’re more popular than Jesus now.” This caused no controversy in the UK and the interview was not published in the USA until late in the summer. In June Capitol released a compilation LP entitled The Beatles Yesterday and Today with a cover photo featuring all four wearing white coats and covered with decapitated baby dolls and pieces of raw meat. They were all laughing and looked like crazed butchers. The band said it was a protest against the Vietnam war. As soon as it was released it was immediately withdrawn by Capitol and replaced with a new photo.

On the left is the photo the Beatles’ wanted and on the right the one Capitol Records chose.

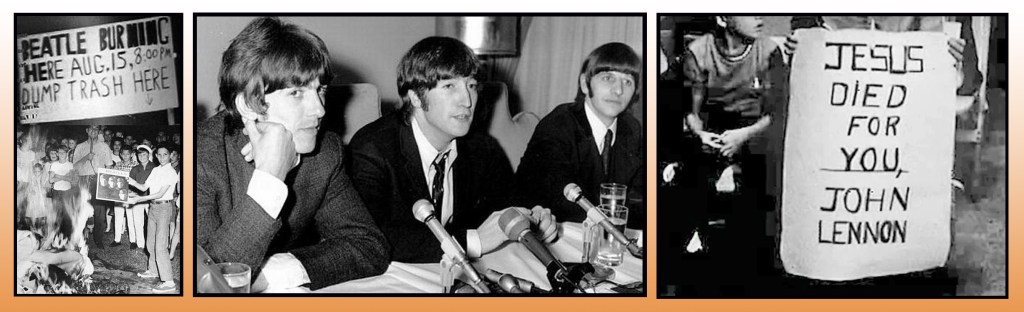

When the Lennon interview was reprinted in the USA that summer, it ignited a huge furore in the southern bible belt which rippled across the country. A disc jockey in Alabama organised a public burning of Beatles material and all this occurred just as they were about to embark on an American tour. The press conference which kicked it off was an uncharacteristically sombre business. Previous Beatles press conferences had all the colourful anarchy of a Marx Brothers movie but this one was weighed down with seriousness. John Lennon, looking pained, reluctantly apologised for causing offence.

Beatles burning in the Bible Belt, a very sombre press conference and a message for John Lennon.

On top of this, they had to flee the Philippines in a hurry after they’d snubbed the first lady, Imelda Marcos, who had invited them to tea. They were clearly unprepared for the angry public reaction. So after their final concert in Candlestick Park in San Francisco, they decided to stop touring and just work in the recording studio.

The Beatles were worshipped in a way which was not entirely healthy and I was as starstruck as everybody else. The hysteria generated by their initial American success in 1964 seemed to have morphed into a slightly different form of hero worship but it was still idolatry plain and simple. I remember sitting around a house in Strawberry which I visited regularly and discussing the Beatles as if they were gods. The house was owned by a woman who was older than me and had two young children. She was separated from her husband and several of my friends and I would gather there regularly to smoke weed and listen to music. She was a guitar playing folk singer who was managed by Frank Werber.

It was at this time that I realised that Mill Valley was becoming a place where people from the rock and roll scene were moving in. Wes Wilson and his wife Eva had a house with a long garden on Sycamore. Bill Graham and guitarist Mike Bloomfield moved into Mill Valley. Mike had left the Butterfield Blues Band and started his own group called The Electric Flag. I once saw his bass player, Harvey Brooks with a big smile on his face, wandering, along Sunnyside near the Post Office one morning. I also heard a remark which chilled my soul. The woman in Strawberry was talking about somebody who was “shooting smack with the Electric Flag.” Nobody in my immediate circle was doing anything like that. It scared me.

I guess that I made a distinction between smoking grass and what I considered to be hard drugs. Somehow I didn’t consider acid to be in that category but through my limited experience with it I knew how powerful it could be. As the summer arrived I became more and more determined that I should have a good experience with LSD. I had become convinced that the reason I wasn’t able to have a good trip was to do with my egotism and that I needed to work on myself. This was not an easy prospect as I had always been a little guy with a big mouth and an even bigger head. The particularly bad trip I’d had the previous year while at the Fillmore was all about loss of control. I felt I had to hold onto my control and was absolutely terrified by the fact that it was oozing away from me in dramatic fashion.

While all this internal drama was going on with me, out in the real world the Vietnam war was, by this time, raging. The daily news had a stream of stories about military action in Vietnam as well as many about students burning their draft cards and huge demonstrations against the war. The police tactics against anti-war protestors became increasingly violent and just as blood was definitely flowing over in Vietnam so too did it flow on the streets of America. David Harris who was married to Joan Baez went to prison for refusing to be drafted into the army. I know a movie producer in Hollywood who pretended he was gay, which he wasn’t, and avoided the draft that way.

My sister Nell was no longer in San Francisco but living in London with her husband and their newborn son Poggy. Nellie and the Hallinan boys had been very active in demonstrations in the city but now had taken her left wing activism to England. The Hallinan boys all remained very active in civil rights and anti-Vietnam war demonstrations

Back in 1965 both Kayo and Ringo Hallinan recruited a small army of tough fighters to form the front line of an anti-war march from Berkeley to Oakland which the Hell’s Angels had announced they were going to break up. Not realising who was in the front of the march, Sonny Barger, Northern California president of the Angels, waded into the crowd thinking they were dealing with pacifists. Barger, shouting abuse, as he pushed his way through the crowd, reached up to pull down a banner. “As he pulled the banner down,” said Ringo, “Kayo hit him with a right fist on one side of his jaw and I delivered a left hook on his other. He went down like a stone. The Angels kept coming, thinking we were a bunch of pacifist wimps. They suddenly found themselves surrounded by a lot of tough guys bent on pounding them. I remember the looks on their faces as they suddenly realised they were in trouble. And they were. We kicked their asses until the Oakland police attacked us and drove us back. Barger lied about that day on many occasions. How they kicked the commies’ asses. It was a fine moment.”

Conn (Ringo) Hallinan on the left before the fight and his brother Terence (Kayo) Hallinan seen punching a Hell’s Angel.

But I stayed away from the big demonstrations as so many turned violent. One day I was hitch hiking out of Mill Valley to the city and got a lift with a young man who was on his way to an anti-war demonstration in Berkeley. He was quite candid in telling me that his motivation was nothing to do with the war but rather it was to meet beautiful young women.

I went to a party in Berkeley and met a guy about my age who was joining the marines the next day. I asked him why and his answer was chilling: “Because I want to kill somebody,” he said. I was so startled by this that I asked him, if it was completely legal, would he kill me? His answer was yes. Now it just happened that I met this guy rather than one of the thousands of young recruits who had no such agenda and were simply doing what the government was ordering them to do.

The whole situation was something I was just not thinking about. My way of dealing with the possibility of being drafted was to smoke another joint. And yet my brother Jim was now in the military and having done his basic training he would be having a stopover in Seattle for a few days en route to Korea. I thought about flying up to see him.

Several guys from my Tam High class of 1965 went into the service and found themselves in Vietnam. Corky Corcoran, Ed Smith and Les Taylor all served over there. Another who was a year younger than me was Ernie Bergman.

Corky, who I had known since 7th grade at Edna Maguire, joined the army in the summer of 1966 and became a paratrooper. Never having been on an airplane before, he was flown to Fort Lewis in Washington where he did his basic training then it was off to Fort Benning in Georgia where he attended jump school. By 1967 he was in Vietnam with the 173rd Airborne Brigade. “We went through the Brigade Jungle School in Bien Hoa,” said Corky, “To prepare us for the upcoming months in the Dak To area of the central highlands.” His job was as a radio teletype operator, part of a 3-man team working from a jeep filled with communications equipment. “We were constantly on the move,” remembers Corky. “ There were some scary times indeed but I made it home in July, 1968.”

Corky Corcoran on the left as a soldier in Vietnam and on the right with his wife in more recent times.

Les Taylor had grown up in a military family, having lived in France, Germany, Turkey and several locations in the USA before arriving at Tam High in his sophomore year. By the time he got to Vietnam he was a qualified helicopter pilot and his initial training began while he was still a student at Tam. On one of his early missions as co-pilot in Vietnam, ferrying men to a combat zone, his commander froze at the controls and he had to take over and fly the copter into the landing area.

Les Taylor in two different military uniforms and on the right a more recent view if him.

Eddie Smith and I had been friends since 6th Grade at Alto. He didn’t go into the service until late in 1967 and went to Vietnam the following year. He said that more American GI’s died between ’68 and ’69 than at any other time in the war. Ed: “I was on a mortar platoon out in the field most of the time. But when we were in base camp, it was just as dangerous. The Vietcong and the regular North Vietnamese Army were shooting mortar rounds and rockets at us all the time. I had plenty of close calls but luckily never got wounded. It was scary as hell and I had nightmares for quite awhile once I got back to the states.”

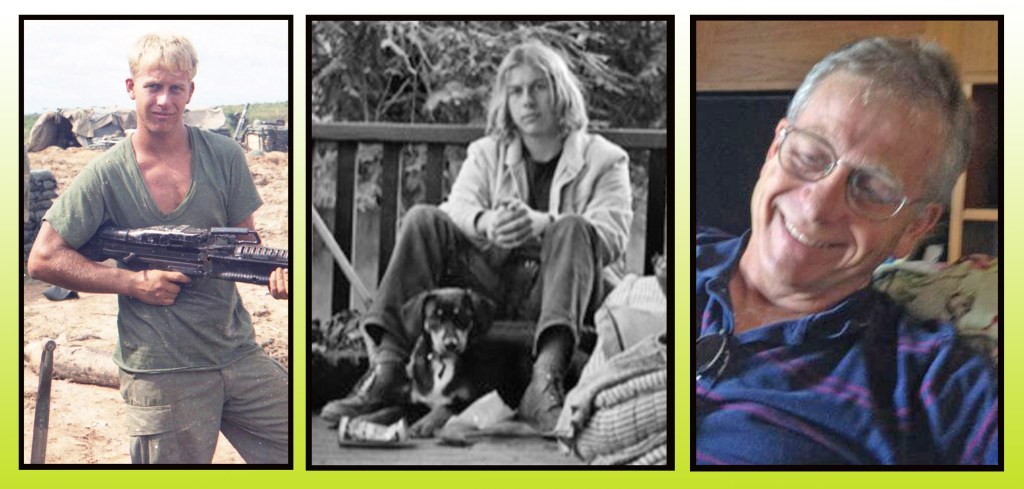

Ed Smith on the left in Vietnam, middle back in Marin after his service and a more recent photo on the right.

Ernie Bergman who was in my brother Jim’s year, joined the Navy in his graduation year of 1966 but didn’t get to Vietnam until April 1967. His first day in Danang was traumatic as he was assigned to be a stretcher bearer for the hospital triage centre where the wounded were brought to see if they could be saved. “What a shock to my whole being!” Says Ernie. “I saw soldiers and marines with all kinds of injuries, lost limbs, large wounds, lots of blood, lots of horror. One guy I was carrying looked like he was on the wrong side of a claymore mine and had 1000 little pockmarks all over his body, face and uniform. Just before I put him down he started shaking so I called the nurse over. I was looking directly into his face and he died right there. Holy Shit! This is REAL! If anything, that first day in Vietnam at the triage center probably had more emotional and mental effect on me than anything else I experienced in my 30 months overseas and in Vietnam.”

On the left a picture of Ernie Bergman in the Navy and on the right more recently at the US Congress in Washington DC.

So while I was smoking weed, dreaming of tangerine trees with marmalade skies, staying up all night to the sound of Larry Miller on KMPX, these guys were experiencing hell on earth in Vietnam. The ride I was on didn’t have much further to go.

To be continued…

Amazon USA

https://www.amazon.com/dp/B085QN73VQ

Amazon UK

https://www.amazon.co.uk/dp/B085QN73VQ